Thursday, Nov 09, 2006

In

One such group working to coordinate the grass-roots based worker takeovers in

Pablo Cormenzana representative from FRETECO and INVEVAL traveled to

M.T.: What happened at INVEVAL that pushed the workers to take over their workplace?

P.C.: INVEVAL started when the owner shut down production in the plant which was formerly called CNV (National Valve Manufacturer) in 2002. The owner of CNV, Sosa Pietri, was part of

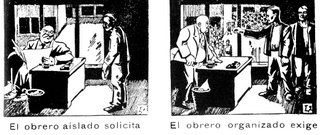

A group of these workers decided to begin a fight to demand that the former owner pay them back what he owed them. Later, this demand transformed into the idea of recovering their jobs and to re-open the company. This stage lasted for two years, from March 2003 until April 2005. A group of about 65 workers continued fighting. They were alone in their fight, visiting labor courts and the labor ministry to demand the salaries that the owner never paid. This long and difficult process had a demoralizing effect on the workers and many abandoned the fight. The group was really dispersed at that time and in December 2004 only one worker continued to camp outside the factory.

Around this time, the former boss decided that it was the perfect moment to empty out the factory. Until December groups of workers had been camping outside the plant’s doors. One night the boss secretly began to transport the semi-constructed valves and tools from the plant. The workers found out that the owner was stealing material from the plant and re-mobilized. This time, more workers camped outside the company’s doors so that the boss wouldn’t continue to ransack the plant. They were thinking ‘this guy left us out in the streets and now he’s leaving with the few things that could be sold to pay us back what he owed us.’

At the very same time, two very important situations developed in

The nationalization of INVEPAL motivated the workers of INVEVAL and they launched a new campaign to get their jobs back. The president decreed the nationalization of CNV, which is to later become INVEPAL-national endogenous valve industry in April 2005.

M.T.: How has the factory been re-organized since the worker take-over?

P.C.: The workers had to fight hard to recover the factory. The factory has been worker run since April 2005, a factory that was abandoned. We’re talking about a huge factory that runs with computers and giant machinery. And yet, the workers were able to make it work. They’re proving the theory that workers can run industry without bosses. Not only are the workers at INVEVAL successfully running a company without bosses or an owner, they’re also doing it without technocrats or bureaucracy from the government. The government has had

little participation in the functioning of the company. The company was solely recovered by the very worker.

M.T. So no professionals stayed on in the plant? How have the workers managed without professionals?

No, only manual workers stayed on in the plant. Middle and high level management abandoned the company along with the boss. They had alliances with the boss. I imagine that the former owner paid them their salaries and indemnity for laying them off and they later found new jobs.

The workers not only recovered a factory by taking over the manual tasks. The workers are also taking charge of the administrative areas. Currently, a group of workers are studying administration at the state-run university. They are proving wrong the theory that workers are unable to run a factory if they don’t have a manager watching every move they make. Factories under worker control function democratically, unlike with a boss. All of the decisions made at INVEVAL are made in a workers’ assembly. The factory is run by worker delegates. The current president of INVEVAL, Jorge Paredes worked in the plant’s stock deposit. The delegates and president were voted democratically by the workers’ assembly. If the delegates and representatives do not fulfill their responsibilities according to what the assembly says, the assembly can revoke the delegate from his or her position. All of the workers make the same salaries, it doesn’t matter if they are truck drivers, line workers or the president of the company. They are putting into practice genuine worker control at INVEVAL.

M.T.: What is the future of the worker controlled factory movement in

P.C: From the perspective of FRETECO we have a very positive outlook for worker control in

There are more than 1,200 business and factories that have been occupied by their workers after bosses and owners abandoned them. President Chávez has nationalized more than 20 companies that are all in different situations. VENEPAL and INVEVAL are at the forefront of the worker controlled factory movement. The working class in